Back in May I started writing a bit on the complicated cultural inheritance of having a diverse ancestry as an American. There is a lot more I want to explore about this topic, so I initially had some hesitance with posting this first draft. But earlier this month I presented on a panel about being a mixed race information professional, and that was the right nudge to make me go back, revise a bit, and release this out into the blog world. I don’t have a lot of answers yet, but I think part of what this is about, is being reflective with a means toward reconciling intergenerational cultural and social inheritances with my own identity in the present.

——–

The only time I can remember feeling Japanese as a kid was the first time I read about the incarceration of Japanese Americans in internment camps in World War II. I learned that Americans who were as much as 1/16th Japanese were taken away and placed in camps. This was shocking to me. My Grandma was Japanese, so I am 1/4 Japanese. I could be put in an internment camp? I wasn’t raised with a sense of being anything other than an American, so the idea that the early 1940s American government would view me as an enemy of the state seemed completely ludicrous.

While I was growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, many of my friends were first generation Americans. It was normal to hear my friends call their parents and speak in a multitude of languages. Going out for pho or boba was a normal high school hang activity and when we hung out at a friend’s house I was well trained to always take my shoes off. My friends clearly identified with and lived a life that was an echo of their parents’ upbringing outside of the U.S. I felt culturally lacking in light of all these parallel American experiences with strong recent cultural ties to places other than the United States. While my friends were Americans plus, I felt only culturally American. I couldn’t call my Dad and talk to him in Japanese. At home we mostly ate food that reflected an inheritance of a mid-20th century American culinary tradition of things that came prepared in boxes and were heated in boxes of the microwave or oven variety.

As a teenager my friends and I loved to take BART from the East Bay to San Francisco. Chinatown was a great place to go out for food, but Japantown felt like little more than a Japan themed shopping center. The only Japanese kid I knew was a child of recent immigrants like the rest of my friends. My Japanese Grandma Machiko passed away in 1994, when I was still in the single digits age range. Even when she was alive we lived far apart. My limited memories of her are only fragments and I often wonder if these are constructed from stories told to me. Not only does my Japanese identity feel false, but so too does my shaky connection to my heritage.

I was given little nudges to be interested in my Japanese background. I had a book about Japan, but none of it resonated with me and it remained a remote curiosity. I might as well have read a book about the Philippines. A couple times my Grandma’s sister and a few cousins came out to visit us in California. They brought gifts, including origami paper. It was a cultural symbol, but I couldn’t connect on an intimate level with little squares of beautifully patterned, colorful paper. I had little squares of Japanese culture, but these were pieces of a mostly impersonal version of the very personally resonating concept of culture.

Sure, I’m Japanese by blood and descent, but how can I be Japanese without the culture?

——–

There’s no doubt that part of my interest in genealogy is due to an early exposure to rich and diverse cultures. I didn’t grow up where either of my parents grew up, and I had friends with such strong traditions and identities. It made me wonder what the pieces were of my own heritage, when I didn’t fit into any of the frames of reference I saw with my friends.

In addition to being Japanese, I also have a strong 1/4 thread of Eastern European from my other Grandma. I can’t say that I feel particularly allied with that history either, but at least I have living relatives in other states that can easily answer questions about our family. I’ve eaten a poticia and know about Polish Easter breakfast. I’ve heard stories about my Catholic great grandpa carrying around rosary beads and shifting his observed birthday to the birthday of the saint he shared his name with. That left only the other half of my identity, a grab bag of Western European heritage, as a mystery.

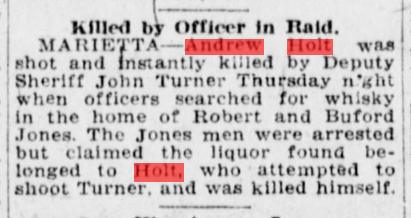

Thankfully I had a head start on the third quarter of my heritage, as my European-American Grandpa got really into genealogy in the 1970s and plotted out an impressive array of British, German, and French ancestors. That left my final mystery quarter from the other side of my family as a detective case for me to tackle. It turns out that I have pretty deep roots in early Tennessee. Learning that I descend from those who owned other humans in Tennessee, and earlier in Virginia and North Carolina, was shocking. I had always assumed that my southern rooted family was financially broke and not morally broken. Yet, the Holts of Tennessee, and the families that married into the Holts, enslaved humans over several generations.

I can’t immediately perceive anything about my life and culture that has come down to me through this heritage. What am I suppose to do to reconcile this legacy guilt? How can I make reparations in the present for being a descendant of a culture that I find repulsive and have no desire to connect with? As much as I long to connect with being Japanese, I also want to distance myself from the horrors perpetrated by my Tennessee ancestors. Yet I feel a guilty desire to know more, to try to understand – who were these people and why were they complicit in this system? In what ways have I been quietly shaped by this hushed inheritance? And can being loud about it be productive?

——-

I moved to Los Angeles ten years ago, and living in Los Angeles led me to feel a renewed pull and interest in any latent Japanese-ness through meeting others who were also partials. I’ve also met several descendants of those that were interned by the United States government in World War II, simply for having Japanese ancestry. I’ve been asked several times about my own family’s internment experience, which always gives me a sense of mild embarrassment. No, no, my ancestors actually were the enemy, as they were still in Japan during WWII. Then that moment of connection with other Japanese descendants becomes a little tarnished. Do we really have a shared history and heritage?

There’s an initial disarming comfort about meeting Japanese-Americans with deep Los Angeles roots, but ultimately Japanese-American history in Los Angeles does not feel like my history. My Grandma was the only one from her family to immigrate to the U.S. and she didn’t really settle down here until the early 1960s. Here wasn’t even the West Coast – she spent the rest of her post-Japan life in suburban Cincinnati, Ohio.

The only place I’ve really “seen” my Grandma is in the documentary Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight. The documentarians seek to bring out the stories of Japanese war brides who “disappeared into America.” The idea of disappearing into America hurts my heart and is maybe part of my motivation to find a way to be more Japanese-American in my own way. This documentary also reaffirms my belief in the importance of being able to see yourself in stories about what it is to be a human. Seeing yourself or your ancestry depicted in the media and in archives is an affirmation of legitimacy.

At the same time, there can be a very fine line between appropriation and cultural pride. Can I be an appropriator of my own culture? Reclaiming ancestral culture that’s been stripped or watered down, without feeling that it is performative – can this be done?

——–

Somehow it feels far easier to claim a heritage that is an assault against humanity. It is strangely somehow easier to feel guilt above other emotions when it comes to cultural background. I can claim the enslaving ancestors because I have no pride in it. From this inheritance I only have my privilege of mostly being perceived as white, made doubly guilty by society’s denial of my Asian-ness. I am a descendant of enslavers, and it is dirty, I have shame, but it is my inherited shame. Yet I don’t feel ownership over my Japanese-ness. Why is this?

Killing or dispossessing another human of their freedom is a pretty timelessly evil thing to do. Some try to absolve past crimes through the historical context argument – weren’t Franklin D. Roosevelt, Andrew Jackson, and Thomas Jefferson “great men”? Yet there were also plenty of contemporaries to these so-called “great men” that saw the human destruction through the layer of societal complacency.

I carry this legacy guilt with me and I can’t travel back in time to change the past. Being cognizant of the damage my ancestors caused, and being thoughtful when framing their actions is a step one. There is no absolution or glorification of their actions and choices. Their purported kindness or generosity to those they enslaved does not change the fact that they were part of a system that held people captive and stole their lives. Being careful to refer to those they enslaved as humans that were enslaved, rather than “slaves,” is a minor language item that restores a modicum of dignity to those they gravely wronged. I grew up taking history classes that referred to people as “slaves.” In adulthood, I learned to start using the term enslaved instead, and it is pretty incredible how much a terminology shift can be a humanity restoring mind flip.

———

I’ve often felt like my body and culture are held hostage by the judgment of outside forces. When I think about the heritage/identity boxes I can place myself in, maybe the answer is that I really am none of the above. That maybe there was some lesson in the frustration I felt every time I had to fill out a form that required me to be “other,” or forced me to choose to ally myself with only one part of my identity. That I have to create something new that is fused from parts both known and acknowledged; unknown and to be explored. The little tendrils drilled down into DNA and words that I hadn’t even realized existed, coupled with the grooved paths I have to create on my own through repetition.

Walk this new path, walk this new path, walk this new path. And one day there will be no more grass on that ground. No more walking through overgrown weeds. It will exist as path alone.

This is the challenge and inheritance of being an American on stolen lands.